Identificação

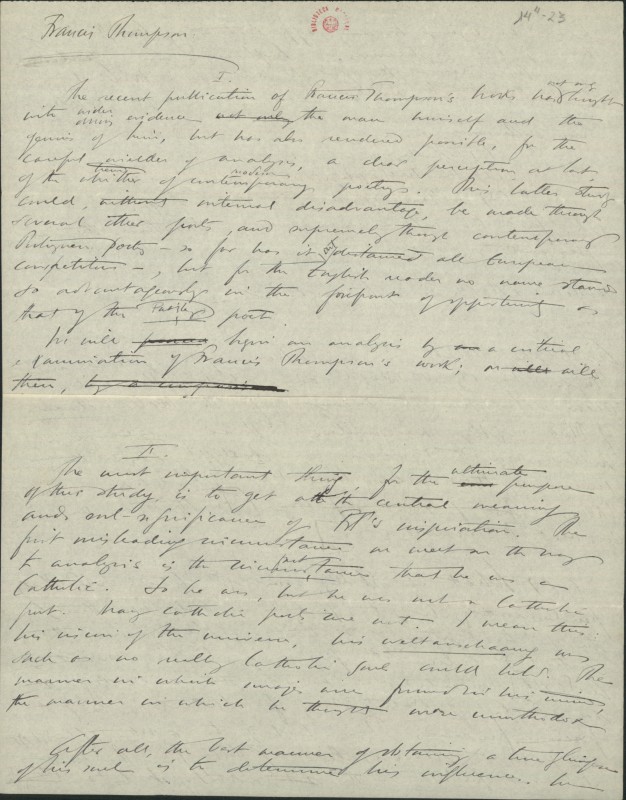

[BNP/E3, 144 – 23-24]

Francis Thompson:

I.

The recent publication of Francis Thompson’s Work has not only brought into wider[1] evidence the man himself and the genius of him, but has also rendered possible, for the careful wielder of analysis, a clear perception, at last, of the whither[2] of the contemporary[3] poetry. This latter study could, without internal disadvantage, be made through several other poets, and supremely through contemporary Portuguese poetry — so far has it out distanced all European competitors —, but for the English reader no name stands so advantageously in the forefront of opportunity as that of the Paisley poet.

We will begin our analysis by a critical examination of Francis Thompson’s work; or will then, {…}

II.

The most important thing, for the ultimate purpose of this study, is to get at the central meaning and soul-significance of Francis Thompson’s inspiration. The first misleading circumstance we meet on the way to analysis is the |circumstance|[4] that he was a Catholic. So he was, but he was not a Catholic poet. Nay Catholic poets are not. I mean this: his vision of the universe, his Weltanschauung was such as no really Catholic soul could hold. The manner in which images were found in his mind, the manner in which he thought were unorthodox.

After all, the best manner of obtaining a true glimpse of his soul is to determine his influences. We

[23v]

mean no injury to any appreciation of his genius by naming his influences. Influences are {…} that reveal the poet to himself. When they are anything else, they are only |copybooks| and there is no poet visible.

These influences are:

(1) Shelley

(2) The “Metaphysicals.”

(3) William Blake and Victor Hugo.

The first two influences are obvious. Sometimes they are flagrant: (Quote)

William Blake is often noticeable {…}

And where Blake is, only absence of reading will omit Hugo. Hugo and Blake are alike. This will seem astonishing to many. Yet the Weltanschauung of Blake and of Hugo are similar. Their conscious outlook upon the universe is different. But their unconscious, their sense-born view of things has a similar basis. [Further on we will see what that similarity is.]

(1) What is Shelley, essentially? What did Shelley fundamentally, bring to poetry? Only one thing: the spiritualization of Nature. Shelley was the central and culminating point of English romanticism. And English romanticism is no more, centrally, than an adoration of Nature rising for intensity in her (the forerunners, Thompson, Cowper) to adoration (Wordsworth, Coleridge) up to divinization (Shelley). The poet who went further in the adoration of Nature was naturally

[24r]

the greatest of all romantics — and highest adoration in divinization. In Shelley there is a fusion of Nature with God. In Shelley the sentiment of soul and the sentiment of Nature become one. Hence his thinking in images. And hence his being the first to employ that curious type of imagery that consists in representing the objective by the subjective, such as says of a flower’s petals, that they are closed like thoughts in a dream.

(2) The Metaphysicals — what did they bring to poetry? This — the sentiment of the interaction of body and soul. Hence the one thing that in them strikes every reader — their complexity.

(3) Victor Hugo brought into poetry this — the humanization of Nature. This is to be carefully distinguished from the spiritualization of it. For the spiritualizer of Nature every thing is valuable spiritually and bodily — it is seen vaguely, its edges are dimmed by perception of the sculpture of it. For the humanizer of Nature, every thing is like a man — body and soul — both important. And his vision of is clear, he takes in clearly the contours of everything — Hence Shelley and Hugo, both think in images, one has subtle, imperceptible images, like {…}; the other clear-cut, neat, violently visible images.

And Blake, as Hugo, humanizes Nature (cf. Hugo Ce que dit; Blake {…}); Blake is on no point so insistent as in the importance of minute particulars.

[24v]

(Victor Hugo’s influence is not very clear in Francis Thompson — because the fundamental influences in him are externally antagonic to Hugo, Shelley and the Metaphysicals.)

Hugo seen through Shelley is Blake, {…} If you weld Shelley and the Metaphysicals, {…}

Francis Thompson’s defects are clear: (1) his constructive incapacity: neither of his influences is a good master in this respect. Hugo, though not confused, is diffused and lengthy. Shelley is the most within-measures, but only because he was Shelley; the basis of his inspiration does not involve equilibrium — far from it. He, in his genius, had it, but the kind of man he was has it not. (2) There is both confusion and diffuseness in his[5] poetry. His diction is over-involved, his development tortuous and slavish, the total-effect of his poems as wholes is miserable. He seems riot. There is no clearness in him anywhere, neither in the detail, nor in the stages, nor in the total poem. Little in the detail, less in the stages, least in the whole structure. Few poems of his stand firm on their structural legs.

He is perhaps a man of genius; he is not very remarkable, though he is often astonishing. There is nothing fundamentally new in him except what is synthetic of former elements. Yet this synthesis is often individual and he is, perhaps, a genius thereby.

[BNP/E3, 144 – 23-24]

Francis Thompson:

I.

A recente publicação da Obra de Francis Thompson não trouxe apenas para uma evidência mais ampla o próprio homem e o seu génio, mas também tornou possível, para o cuidadoso manejador da análise, uma percepção clara, finalmente, da proveniência da poesia contemporânea. Este último estudo poderia, sem desvantagem interna, ser feito por vários outros poetas, e supremamente pela poesia portuguesa contemporânea - até onde distanciou todos os concorrentes europeus -, mas para o leitor inglês nenhum nome se destaca tão vantajosamente na vanguarda da oportunidade como o do poeta Paisley.

Começaremos a nossa análise por um exame crítico da obra de Francis Thompson; ou então, {…}

II.

O mais importante, para o propósito final deste estudo, é chegar ao significado central e à significação de alma da inspiração de Francis Thompson. A primeira circunstância enganosa que encontramos no caminho da análise é a |circunstância| de que ele era católico. Ele era católico, mas não um poeta católico. Não, não existem poetas católicos. Quero dizer o seguinte: a sua visão do universo, a sua Weltanschauung era algo que nenhuma alma realmente católica poderia suportar. A maneira pela qual as imagens foram encontradas na sua mente, a maneira pela qual ele pensava, não eram ortodoxas.

Afinal, a melhor maneira de obter um verdadeiro vislumbre da sua alma é determinar as suas influências. Nós

[23v]

não queremos significar nenhum dano a qualquer apreciação do seu génio ao nomear as suas influências. As influências são {…} que revelam o poeta a si mesmo. Quando são qualquer outra coisa, são apenas |cadernos de cópias| e não há nenhum poeta visível.

Essas influências são:

(1) Shelley

(2) Os “Metafísicos.”

(3) William Blake e Victor Hugo.

As duas primeiras influências são óbvias. Às vezes, são flagrantes: (citação)

William Blake costuma notar-se {…}

E onde Blake está, apenas a ausência de leitura irá omitir Hugo. Hugo e Blake são semelhantes. Isso parecerá surpreendente para muitos. No entanto, a Weltanschauung de Blake e de Hugo é semelhante. A sua visão consciente do universo é diferente. Mas o seu inconsciente, a sua visão das coisas nascida dos sentidos tem uma base semelhante. [Mais adiante veremos o que é essa semelhança.]

(1) O que é Shelley, essencialmente? O que Shelley fundamentalmente trouxe para a poesia? Só uma coisa: a espiritualização da Natureza. Shelley foi o ponto central e culminante do romantismo inglês. E o romantismo inglês não é mais, centralmente, do que uma adoração da Natureza crescendo em intensidade nela (os precursores, Thompson, Cowper) da adoração (Wordsworth, Coleridge) até à divinização (Shelley). O poeta que foi mais longe na adoração da Natureza foi naturalmente

[24r]

o maior de todos os românticos - e a maior adoração na divinização. Em Shelley, há uma fusão da Natureza com Deus. Em Shelley, o sentimento da alma e o sentimento da Natureza tornam-se um. Daí o seu pensar em imagens. E daí ser o primeiro a empregar aquele curioso tipo de imagética que consiste em representar o objectivo pelo subjectivo, como se diz das pétalas de uma flor, que estão fechadas como pensamentos num sonho.

(2) Os metafísicos - o que eles trouxeram para a poesia? Isto - o sentimento da interacção do corpo e da alma. Daí a única coisa que neles impressiona todo leitor - a sua complexidade.

(3) Victor Hugo trouxe para a poesia isto - a humanização da Natureza. Isto deve ser cuidadosamente diferenciado da espiritualização dela. Para o espiritualizador da Natureza, tudo é valioso espiritual e corporalmente - é visto vagamente, as suas bordas são obscurecidas pela percepção da escultura dele. Para o humanizador da Natureza, tudo é como um homem - corpo e alma - ambos importantes. E sua visão de é clara, ele capta com clareza os contornos de tudo - Daí Shelley e Hugo, ambos pensam em imagens, um tem imagens subtis, imperceptíveis, como {…}; o outro imagens bem-definidas, nítidas e violentamente visíveis.

E Blake, como Hugo, humaniza a Natureza (cf. Hugo Ce que dit; Blake {…}); em nenhum ponto Blake é tão insistente quanto na importância de detalhes minuciosos.

[24v]

(A influência de Victor Hugo não é muito clara em Francis Thompson - porque as influências fundamentais nele são externamente antagónicas a Hugo, Shelley e aos Metafísicos.)

Hugo visto através de Shelley é Blake, {…} Se soldar Shelley e os Metafísicos, {…}

Os defeitos de Francis Thompson são claros: (1) sua incapacidade construtiva: nenhuma de suas influências é um bom mestre a esse respeito. Hugo, embora não confuso, é difuso e extenso. Shelley é o que está mais dentro dos limites, mas apenas porque ele era Shelley; a base de sua inspiração não envolve equilíbrio - longe disso. Ele, no seu génio, possuía-o, mas o tipo de homem que ele era, não. (2) Há confusão e difusão na sua poesia. A sua dicção é excessivamente envolvente, o seu desenvolvimento tortuoso e servil, o efeito total dos seus poemas como todos é miserável. Ele parece rebelde. Não há clareza nele em parte alguma, nem nos detalhes, nem nos estágios, nem no poema total. Pouco nos detalhes, menos ainda nos estágios, menos de tudo na estrutura total. Poucos poemas dele permanecem firmes em suas pernas estruturais.

Ele é talvez um homem de génio; ele não é muito notável, embora muitas vezes seja surpreendente. Não há nada de fundamentalmente novo nele, excepto o que é sintético de elementos anteriores. No entanto, essa síntese é frequentemente individual e, por causa disso, ele talvez seja um génio.

[1] wider /obvious\

[2] whither /trend\

[3] contemporary /modern\

[4] |circumstance| /fact\

[5] his /Francis Thompson’s\