Identificação

[19 – 88]

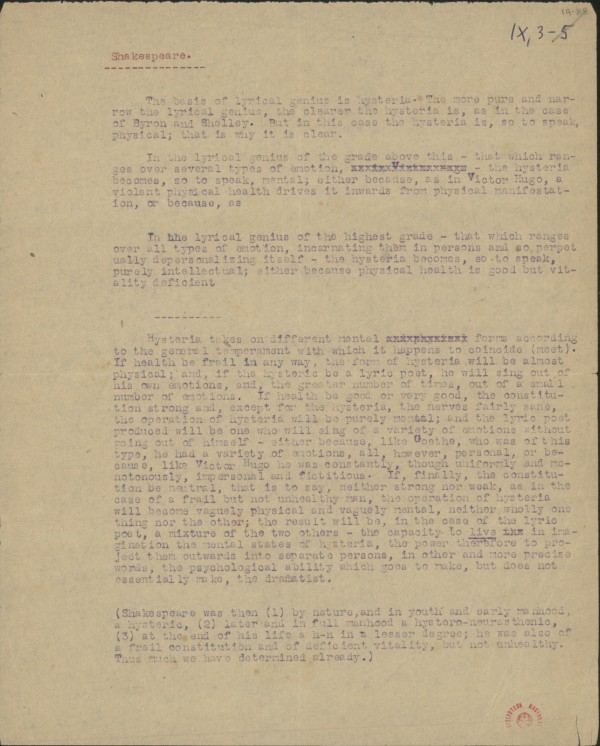

Shakespeare.

The basis of lyrical genius is hysteria. The more pure and narrow the lyrical genius, the clearer the hysteria is, as in the case of Byron and Shelley. But in this case the hysteria is, so to speak, physical; that is why it is clear.

In the lyrical genius of the grade above this – that which ranges over several types of emotion – the hysteria becomes, so to speak, mental; either because, as in Victor Hugo, a violent physical health drives it inwards from physical manifestation, or because, as {…}

In the lyrical genius of the highest grade – that which ranges over all types of emotion, incarnating them in persons and so perpetually depersonalizing itself – the hysteria becomes, so to speak, purely intellectual; either because physical health is good but vitality deficient {…}

----------

Hysteria takes on different mental forms according to the general temperament with which it happens to coincide[1]. If health be frail in any way, the form of hysteria will be almost physical; and, if the hysteric be a lyric poet, he will sing out of his own emotions, and, the greater number of times, out of a small number of emotions. If health be good or very good, the constitution strong and, except for the hysteria, the nerves fairly sane, the operation of hysteria will be purely mental; and the lyric poet produced will be one who will sing of a variety of emotions without going out of himself – either because, like Goethe, who was of this type, he had a variety of emotions, all, however, personal, or because, like Victor Hugo he was constantly, though uniformly and monotonously, impersonal and fictitious. If, finally, the constitution be neutral, that is to say, neither strong nor weak, as in the case of a frail but not unhealthy man, the operation of hysteria will become vaguely physical and vaguely mental, neither wholly one thing nor the other; the result will be, in the case of the lyric poet, a mixture of the two others – the capacity to live in imagination the mental states of hysteria, the power therefore to project them outwards into separate persons, in other and more precise words, the psychological ability which goes to make, but does not essentially make, the dramatist.

(Shakespeare was then (1) by nature, and in youth and early manhood, a hysteric, (2) later and in full manhood a hystero-neurasthenic, (3) at the end of his life a hystero-neurasthenic in a lesser degree; he was also of a frail constitution and of deficient vitality, but not unhealthy. Thus much we have determined already.)

[19 – 88]

Shakespeare.

A base do génio lírico é a histeria. Quanto mais puro e estreito o génio lírico, mais clara é a histeria, como no caso de Byron e Shelley. Mas neste caso a histeria é, por assim dizer, física; é por isso que é clara.

No génio lírico do grau acima deste – aquele que abrange vários tipos de emoção – a histeria torna-se, por assim dizer, mental; seja porque, como em Victor Hugo, uma saúde física violenta, partindo da manifestação física, o direcciona para dentro ou porque, como {…}

No génio lírico do grau superior – aquele que abrange todos os tipos e emoção, incarnando-as em pessoas e, desse modo, despersonalizando-se a si próprio perpetuamente – a histeria torna-se, por assim dizer, puramente intelectual; seja porque a saúde física é boa, mas vitalmente deficiente {…}

----------

A histeria assume diferentes formas mentais de acordo com o temperamento geral com o qual sucede coincidir. Se a saúde for de algum modo frágil, a forma de histeria será quase física; e, se o histérico for um poeta lírico, cantará a partir das suas próprias emoções e, na maioria dos casos, a partir de um número restrito de emoções. Se a saúde for boa ou muito boa, a constituição forte e, excepto pela histeria, os nervos suficientemente sãos, a operação da histeria será puramente mental; e o poeta lírico produzido será alguém que cantará uma variedade de emoções sem sair de si próprio – seja porque, como Goethe, que era deste tipo, tenha uma variedade de emoções, todas, porém, pessoais ou porque, como Victor Hugo, seja constantemente, embora uniformemente e monotonamente, impessoal e fictício. Se, por fim, a constituição for neutra, isto é, nem forte nem fraca, como no caso de um homem frágil mas saudável, a operação da histeria tornar-se-á vagamente física e vagamente mental, nem totalmente uma coisa nem a outra; o resultado será, no caso do poeta lírico, uma mistura dos outros dois – a capacidade de viver na imaginação os estados mentais da histeria, portanto, a potência de projectá-los para fora em diferentes pessoas, em outras palavras mais precisas, a capacidade psicológica que constitui, embora não constitua essencialmente, o dramaturgo.

(Shakespeare era, por conseguinte, (1) por natureza, na juventude e no princípio da idade adulta, um histérico, (2) mais tarde e em plena idade adulta um histérico-neurasténico, (3) no fim da sua vida, um histérico-neurasténico num grau menor; possui também uma constituição frágil e com deficiente vitalidade, mas saudável. É isto que já determinámos.)

[1] coincide /(meet)\