Identificação

[19 – 74]

Erostratus.

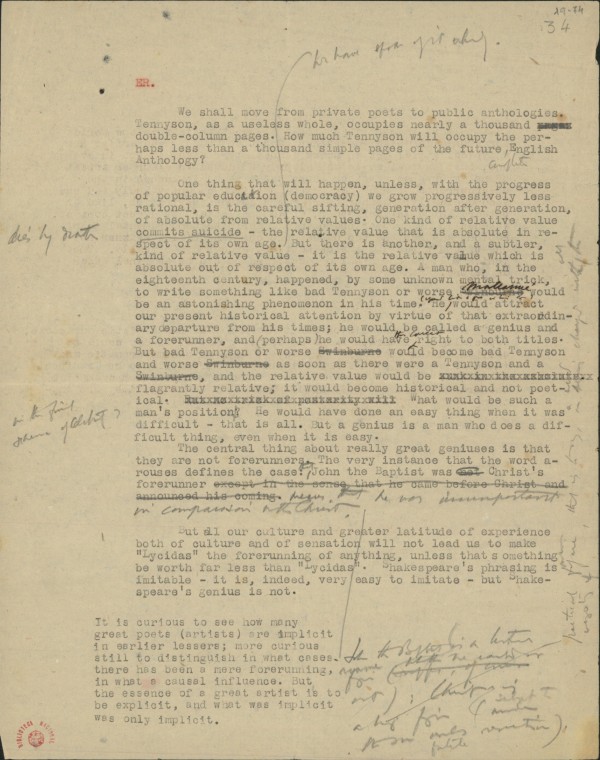

We shall move from private poets to public anthologies. Tennyson, as a useless whole, occupies nearly a thousand double-column pages. How much Tennyson will occupy the perhaps less than a thousand simple pages of the future complete English Anthology?

One thing that will happen, unless, with the progress of popular education[1] we grow progressively less rational, is the careful sifting, generation after generation, of absolute from relative values. One kind of relative value commits suicide[2] – the relative value that is absolute in respect of its own age. We have spoken of it above. But there is another, and a subtler, kind of relative value – it is the relative value which is absolute out of respect of its own age. A man who, in the eighteenth century, happened, by some unknown mental trick, to write something like bad Tennyson or worse Mallarmé, would be an astonishing phenomenon in his time. He (ignored like a genius is in his age) would attract our present historical attention by virtue of that extraordinary departure from his times; he would be called a genius and a forerunner, and[3] he would have the concrete right to both titles. But bad Tennyson or worse Mallarmé would become bad Tennyson and worse Mallarmé as soon as there were a Tennyson and a Mallarmé, and the relative value would be flagrantly relative; it would become historical and not poetical. What would be such a man’s position in the final scheme of celebrity? He would have done an easy thing when it was difficult – that is all. But a genius is a man who does a difficult thing, even when it is easy.

The central thing about really great geniuses is that they are not forerunners. The very instance that the word arouses defines the case: that John the Baptist was Christ’s forerunner means that he was unimportant in comparison with Christ. John the Baptist is a historical name[4] (whether he existed or not); Christ is a living figure (under[5] the same useless reservation).

But all our culture and greater latitude of experience both of culture and of sensation will not lead us to make “Lycidas” the forerunning of anything, unless that something be worth far less than “Lycidas”. Shakespeare’s phrasing is imitable – it is, indeed, very easy to imitate – but Shakespeare’s genius is not.

It is curious to see how many great poets[6] are implicit in earlier lessers; more curious still to distinguish in what cases there has been a mere forerunning, in what a casual influence. But the essence of a great artist is to be explicit, and what was implicit was only implicit.

[74v]

There is hardly any, if any, great artist in the world for whom a definite forerunner cannot be found. Each artist has a typical style; yet in almost every case, if not in every one, that typical style was already shadowed in a former artist of no importance. Whether there was a vague influence in the undercurrents of the age, which the first caught vaguely and the second clearly; whether there was a chance inspiration, like an outward thing in the former, which the latter, by direct contact, wakened in his proper brain[7] into a definite temperamental[8] inspiration; whether the two cases were consubstantial – not one of the hypotheses[9] matters, except historically. The genius will be the final product; and he will be as final after as before.[10]

The practicality of our times has had some artistic advantage, especially in literature. No detective story of to-day could be written in the style of “Tom Jones”. We have become dramatic (however bad our dramas may be) and wish our novels to be as direct as dramas. This is a natural and a sane exigency. (Such dramas as Bernard Shaw’s are survivals of an earlier tendency; they are anything but modern in their delaying thinkingness).

[19 – 74]

Heróstrato.

Devemos agora passar dos poetas privados para as antologias públicas. Tennyson, inútil no seu todo, ocupa quase mil páginas de duas colunas. Quanto de Tennyson ocupará a futura Antologia Inglesa completa que terá talvez menos do que mil páginas simples?

Uma coisa que acontecerá, a menos que com o progresso da educação popular nos tornemos progressivamente menos racionais, é o cuidadoso peneirar, geração após geração dos valores absolutos e dos relativos. Um tipo de valor relativo comete suicídio – o valor relativo que é absoluto a respeito da sua própria época. Já falámos sobre isso acima. Mas existe outro tipo de valor relativo, mais subtil, – é o valor relativo que é absoluto em relação à sua própria época. Um homem que, no século XVIII, tivesse, por meio de algum truque mental desconhecido, escrito algo como um mau Tennyson ou um pior Mallarmé, teria sido um fenómeno espantoso no seu tempo. Ele (ignorado como um génio é na sua época) teria atraído a nossa atenção histórica presente em virtude dessa extraordinária distância relativamente ao seu tempo; teria sido chamado de génio e de precursor e teria tido o direito a ambos os títulos. Mas o mau Tennyson e o pior Mallarmé ter-se-iam tornado mau Tennyson e pior Mallarmé assim que existisse um Tennyson e um Mallarmé e o valor relativo seria flagrantemente relativo; ter-se-ia tornado histórico e não poético. Qual seria a posição de um tal homem no esquema final da celebridade? Ele teria feito algo fácil quando era difícil – e isso é tudo. Mas um génio é um homem que faz algo difícil, mesmo quando é fácil.

Aquilo que é central em génios realmente grandes é que eles não são precursores. O próprio exemplo que a palavra desperta define o caso: que João Baptista foi precursor de Cristo significa que não foi importante em comparação com Cristo. João Baptista é um nome histórico (tenha existido ou não); Cristo é uma figura viva (sob a mesma ressalva inútil).

Mas toda a nossa cultura e maior latitude de experiência tanto da cultura quanto da sensação não nos conduzirá a fazer de “Lycidas” o percursor de nada, a menos que isso tenha menor valor do que “Lycidas”. O fraseado de Shakespeare é imitável – é, de facto, muito fácil de imitar – mas não o génio de Shakespeare.

É curioso ver quantos dos grandes poetas estão implícitos em anteriores poetas menores; mais curioso ainda é distinguir em que casos foram meros percursores e em que casos houve uma influência casual. Mas a essência de um grande artista é ser explícito e o que era implícito era apenas implícito.

[74v]

Dificilmente existe algum, se é que há algum, grande artista no mundo para quem não se possa encontrar um percursor definido. Cada artista tem um estilo típico; contudo, em quase todos os casos, se não mesmo em todos, esse estilo típico já se encontrava esboçado num artista anterior sem qualquer importância. Se havia uma vaga influência nas subcorrentes da época, que o primeiro captou vagamente e o segundo claramente; se foi uma mera inspiração ocasional, como algo externo no anterior, que o posterior, por contacto directo, despertou no seu próprio cérebro numa inspiração temperamental definida; se os dois casos foram consubstanciais – nenhuma das hipóteses interessa, excepto historicamente. O génio será o produto final; e será tão final antes quanto depois.

A pragmaticidade do nosso tempo tem tido alguma vantagem artística, especialmente em literatura. Nenhuma história policial de hoje poderia ser escrita no estilo de “Tom Jones”. Tornámo-nos dramáticos (por piores que os nossos dramas sejam) e desejamos que os nossos romances sejam tão directos quanto os dramas. Isto é uma exigência natural e sã. (Os dramas como os de Bernard Shaw são resquícios de uma tendência anterior; são tudo menos modernos na sua vagarosa meditatividade).

[1] popular education /(democracy)\

[2] commits suicide /dies by death\

[3] and /(perhaps)\

[4] name /figure\

[5] living figure /poetical figure /name\, that is to say, a being /a word\ charged with all the mystery of {…}\ (under /subject to\

[6] poets /(artists)\

[7] proper /temperamental\ brain

[8] temperamental /inner\

[9] the /(three)\ hypotheses

[10] and he will be as final after as before. /even if he comes afterwards.\

Classificação

Dados Físicos

Dados de produção

Dados de conservação

Palavras chave

Documentação Associada

Publicação integral: Fernando Pessoa, Heróstrato e a Busca da Imortalidade, edição de Richard Zenith, Lisboa, Assírio & Alvim, 2000, pp. 192-194.