Identificação

[19 – 47–49]

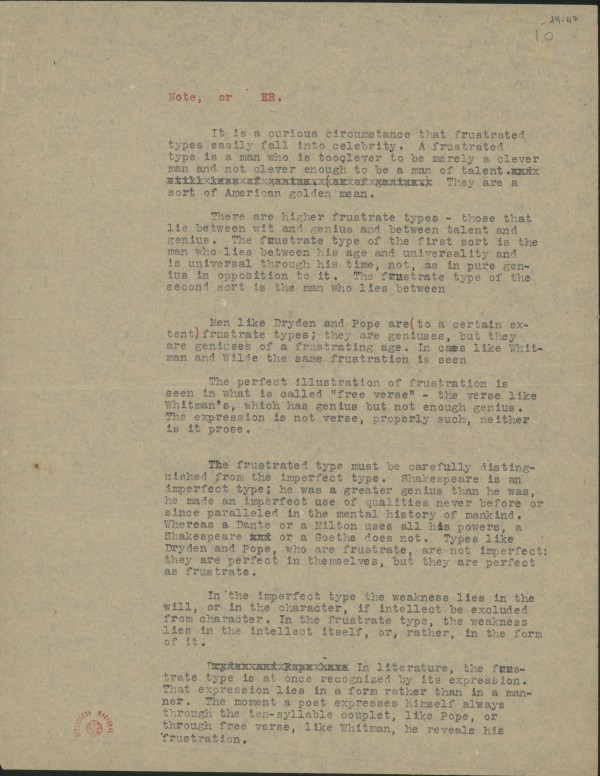

Note, or Erostratus.

It is a curious circumstance that frustrated types easily fall into celebrity. A frustrated type is a man who is too clever to be merely a clever man and not clever enough to be a man of talent. They are a sort of American golden mean.

There are higher frustrate types — those that lie between wit and genius and between talent and genius. The frustrate type of the first sort is the man who lies between his age and universality and is universal through his time, not, as in pure genius, in opposition to it. The frustrate type of the second sort is the man who lies between {…}

Men like Dryden and Pope are (to a certain extent) frustrate types; they are geniuses, but they are geniuses of a frustrating age. In cases like Whitman and Wilde the same frustration is seen {…}

The perfect illustration of frustration is seen in what is called “free verse” – the verse like Whitman’s, which has genius but not enough genius. The expression is not verse, properly such, neither is it prose.

The frustrated type must be carefully distinguished from the imperfect type. Shakespeare is an imperfect type; he was a greater genius than he was, he made an imperfect use of qualities never before or since paralleled in the mental history of mankind. Whereas a Dante or a Milton uses all his powers, a Shakespeare or a Goethe does not. Types like Dryden and Pope, who are frustrate, are not imperfect: they are perfect in themselves, but they are perfect as frustrate.

In the imperfect type the weakness lies in the will, or in the character, if intellect be excluded from character. In the frustrate type, the weakness lies in the intellect itself, or, rather, in the form of it.

In literature, the frustrate type is at once recognized by its expression. That expression lies in a form rather than in a manner. The moment a poet expresses himself always through the ten-syllable couplet, like Pope, or through free verse, like Whitman, he reveals his frustration.

[48r]

There would seem to be in men like Ben Jonson and Pope something like mere talent, not genius. Yet there is genius, except that that genius is talent.

The frustrate type offers the one chance of celebrity in its own age to men of genius. By putting genius into wit or into talent, these men become understood as geniuses by their own times. They become rightly understood as geniuses. That is to say, they must be distinguished from mere wits, who may be called geniuses because of their cleverness, but who are not geniuses at all.

The imperfect type consists of two sub-types – the man who has genius and wit but no talent, thus jumping an intermediate step, Shakespeare and Goethe being the supreme examples; and the man who has simple genius, without the balancing element of either talent or wit, as in the case of Blake. These are the strange singers {…}

A case like Poe. Poe had genius. Poe had talent for he has great reasoning powers, and reasoning is the formal expression of talent. (???)

Wit is divided into three types – wit proper, reasoning and criticism; talent into two types – constructive ability and philosophical ability; genius is of only one type – originality. The three mental degrees form a pyramid.

When there is genius without either talent or cleverness, the genius becomes consubstantial with insanity. This is the case of men like Blake. They present a universality; else they would not be geniuses, but mere madmen; but they present, by the very nature of their case, a limited universality, they figure an experience of all times, but common in all times to a very few men in each. These men, being geniuses, become immortal, but they will always be immortal at home, where they will not be seen unless they be visited. A Blake or a Shelley can never appeal to the generality of any age; they have the beauty of rarities rather than the beauty of perfect things. They may become, at one time or another, so long as that time is not theirs, very widely popular, but they will become so only by suggestion, decent coterieness, critical excitement.

Out of the diverse unions of any two or more of these six qualities and the diverse degrees of any quality in the union, are all mental types evolved.

[49r]

We have types like Poe – genius and one element (reasoning) of cleverness. (His philosophical ability was a fiction, got out of dreams, and this is shown by his incapacity to reason clearly on philosophical matters, in spite of his admirable reasoning powers. His criticism, too, is false; it is built out of reasoning, as in his celebrated self-delusion of the building of The Raven, no very remarkable poem, by the bye). We have types like Lamb, genius and one element (wit). We have types like Coleridge – genius and criticism. – All these men who balance genius with only one of the qualities of cleverness are on the verge of madness; and the three cases which serve as examples show this very clearly.

It must not be supposed that mental types describable by the union of the same elements are necessarily alike. Genius is of several types and wit, reasoning (least) and criticism of several types too. Thus, Coleridge is a union of genius and criticism; but Wilde is also a union of genius and criticism.

(Wrong: Wilde had both wit and criticism)

Analyse all this well. Another hypothesis:

Cleverness consists of: (a) external observation, (b) internal observation, (c) reasoning.

or

Cleverness consists of: (a) external observation, (b) internal observation, (c) criticism.

Talent consist of (a) reasoning, (b) constructive ability, (c) {…}

Cleverness: (a) External observation, (b) internal observation, (c) criticism, (d) reasoning, (e) wit (i.e. expression)

Talent: (f) constructive ability, (g) philosophical ability, (h) {…}

Cleverness: (a) power of expression, (b) power of comparison, (c) power of reasoning.

Talent: (a) philosophical ability, (b) constructive ability.

Genius: (a) originality, only.

[19 – 47-49]

Nota, ou Heróstrato.

É uma circunstância curiosa que os tipos frustrados facilmente caiem na celebridade. Um tipo frustrado é um homem que é demasiado inteligente para ser meramente um homem inteligente e não suficientemente inteligente para ser um homem de talento. São uma espécie de meio-termo áureo americano.

Existem tipos frustrados superiores – aqueles que se encontram entre a sagacidade e o génio e entre o talento e o génio. A primeira espécie de tipo frustrado é o homem que se encontra entre a sua época e a universalidade e é universal através do seu tempo, não, como no puro génio, em a oposição a ele. A segunda espécie de tipo frustrado é o homem que se encontra entre {…}

Homens como Dryden e Pope são (em certa medida) tipos frustrados; eles são génios, mas são génios de uma época frustrante. Em casos como Whitman e Wilde vemos a mesma frustração {…}

A ilustração perfeita da frustração pode ser constatada naquilo a que se chama “verso livre” – o verso livre como o de Whitman, que tem génio, mas não génio suficiente. A expressão não é verso, propriamente tal, nem é prosa.

O tipo frustrado deve ser cuidadosamente distinguido do tipo imperfeito. Shakespeare é um tipo imperfeito; ele era um génio maior do que foi, fez um uso imperfeito de qualidades que nunca antes existiram ou sem paralelo na história mental da humanidade. Enquanto um Dante ou um Milton usam todas as suas potências, um Shakespeare ou um Goethe não o fazem. Tipos como Dryden e Pope, que são frustrados, não são imperfeitos: são em si mesmos perfeitos, mas são perfeitos enquanto frustrados.

Nos tipos imperfeitos a fraqueza reside na vontade, ou no carácter, se se excluir o intelecto do carácter. No tipo frustrado a fraqueza reside no próprio intelecto, ou antes na sua forma.

Na literatura o tipo frustrado é logo reconhecido pela sua expressão. Essa expressão encontra-se mais numa forma do que numa maneira. No momento em que um poeta se expressa sempre através da cópula decassilábica, como Pope, ou através do verso livre, como Whitman, revela-se a sua frustração.

[48r]

Pareceria existir em homens como Ben Jonson e Pope algo como mero talento e não génio. Contudo, existe génio, excepto que esse génio é talento.

O tipo frustrado oferece a única oportunidade de celebridade na sua própria época para os homens de génio. Ao depositar o génio na sagacidade ou no talento, estes homens tornam-se compreendidos como génios no seu próprio tempo. Tornam-se correctamente compreendidos como génios. Isto é, devem ser distinguidos dos meros sagazes, que poderão ser chamados génios por causa da sua inteligência, mas que não são, de todo, génios.

O tipo imperfeito consiste em dois sub-tipos – o homem que tem génio e sagacidade, mas nenhum talento, saltando assim um degrau intermédio, sendo Shakespeare e Goethe os exemplos supremos; e o homem que tem génio simples, sem o elemento balanceador do talento ou da sagacidade, como no caso de Blake. Estes são os cantores estranhos {…}

Um caso como Poe. Poe tinha génio. Poe tinha talento, pois tem grande capacidade de raciocínio e o raciocínio é a expressão formal do talento. (???)

A sagacidade encontra-se dividida em três tipos – a sagacidade propriamente dita, o raciocínio e a crítica; o talento em dois tipos – a capacidade construtiva e a habilidade filosófica; o génio é de um tipo apenas – a originalidade. Os três degraus mentais de uma pirâmide.

Quando existe génio sem talento ou inteligência, o génio torna-se consubstancial com a loucura. Este é o caso de homens como Blake. Eles apresentam uma universalidade; de outro modo, não seriam génios, mas meros loucos; mas eles apresentam, pela própria natureza do seu caso, uma universalidade limitada, eles configuram uma experiência de todos os tempos, mas comum, em todos os tempos, a muito poucos homens. Estes homens, sendo génios, tornam-se imortais, mas serão sempre imortais em casa, onde não serão vistos a menos que sejam visitados. Um Blake ou um Shelley nunca podem apelar para a generalidade de uma determinada época; eles têm a beleza das raridades e não a beleza das coisas perfeitas. Podem tornar-se muito populares numa ou noutra época, desde que essa época não seja a sua, mas tornar-se-ão apenas pela sugestão, por meio de um círculo decente, por entusiamo crítico.

Das diversas uniões de duas ou mais destas seis qualidades e dos diversos graus de qualquer uma das qualidades na união, desenvolvem-se todos os tipos mentais.

[49r]

Temos tipos como Poe – génio e um elemento (raciocínio) de inteligência. (A sua habilidade filosófica era uma ficção, nascida dos sonhos, e isto fica evidente pela sua incapacidade de raciocinar claramente em assuntos filosóficos, apesar dos seus admiráveis poderes de raciocínio. A sua crítica também é falsa; é construída sobre o raciocínio, como na sua célebre auto-ilusão da construção de O Corvo, um poema que, digamos, não é admirável). Temos tipos como Lamb, génio e um elemento (sagacidade). Temos tipos como Coleridge – génio e crítica. – Todos estes homens, que balanceiam o génio com apenas uma das qualidades da inteligência, encontram-se à beira da loucura; e os três casos que servem como exemplos mostram-no claramente.

Não deve supor-se que os tipos mentais descritíveis pela união dos mesmos elementos são necessariamente iguais. O génio é de diversos tipos e a sagacidade, o raciocínio (menos) e a crítica também são de diversos tipos. Assim, Coleridge é a união de génio e crítica; mas Wilde também é a união de génio e crítica.

(Errado: Wilde é ambos sagacidade e crítica)

Analisar tudo isto muito bem. Outra hipótese:

Inteligência consiste em: (a) observação externa, (b) observação interna, (c) raciocínio.

ou

Inteligência consiste em: (a) observação externa, (b) observação interna, (c) crítica.

Talento consiste em (a) raciocínio, (b) habilidade construtiva, (c) {…}

Inteligência: (a) observação externa, (b) observação interna, (c) crítica, (d) raciocínio, (e) sagacidade (i.e. expressão)

Talento: (f) habilidade construtiva, (g) habilidade filosófica, (h) {…}

Inteligência: (a) poder de observação, (b) poder de comparação, (c) poder de raciocínio.

Talento: (a) habilidade filosófica, (b) habilidade construtiva.

Génio: (a) originalidade, apenas.

Classificação

Dados Físicos

Dados de produção

Dados de conservação

Palavras chave

Documentação Associada

Publicação integral: Fernando Pessoa, Heróstrato e a Busca da Imortalidade, edição de Richard Zenith, Lisboa, Assírio & Alvim, 2000, pp. 183-186; 207.