Identificação

[19 – 41]

Erostratus.

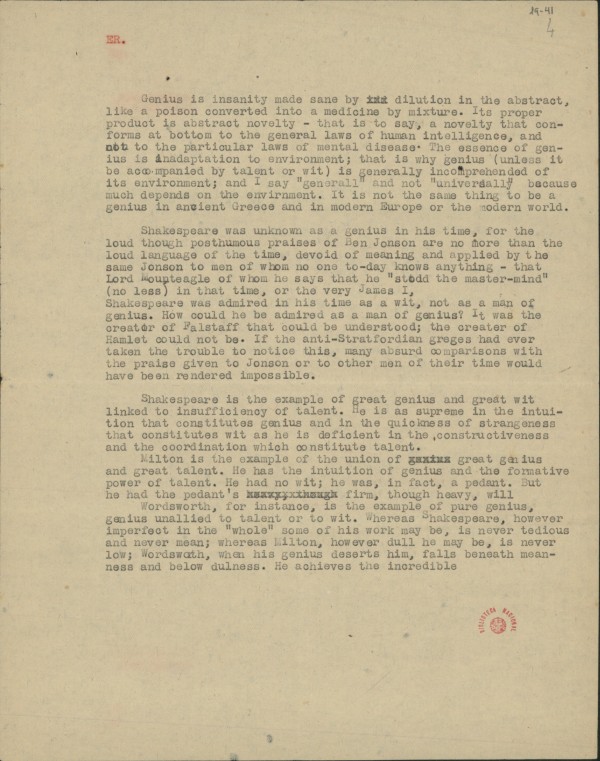

Genius is insanity made sane by dilution in the abstract, like a poison converted into a medicine by mixture. Its proper product is abstract novelty – that is to say, a novelty that conforms at bottom to the general laws of human intelligence, and not to the particular laws of mental disease. The essence of genius is inadaptation to environment; that is why genius (unless it be accompanied by talent or wit) is generally incomprehended of its environment; and I say “generally” and not “universally” because much depends on the environment. It is not the same thing to be a genius in ancient Greece and in modern Europe or the modern world.

Shakespeare was unknown as a genius in his time, for the loud though posthumous praises of Ben Jonson are no more than the loud language of the time, devoid of meaning and applied by the same Jonson to men of whom no one to-day knows anything – that Lord Mounteagle of whom he says that he “stood the master-mind” (no less) in that time, or the very James I, {…} Shakespeare was admired in his time as a wit, not as a man of genius. How could he be admired as a man of genius? It was the creator of Falstaff that could be understood; the creator of Hamlet could not be. If the anti-Stratfordian greges had ever taken the trouble to notice this, many absurd comparisons with the praise given to Jonson or to other men of their time would have been rendered impossible.

Shakespeare is the example of great genius and great wit linked to insufficiency of talent. He is as supreme in the intuition that constitutes genius and in the quickness of strangeness that constitutes wit as he is deficient in the constructiveness and the coordination which constitute talent.

Milton is the example of the union of great genius and great talent. He has the intuition of genius and the formative power of talent. He had no wit; he was, in fact, a pedant. But he had the pedant’s firm, though heavy, will.

Wordsworth, for instance, is the example of pure genius, genius unallied to talent or to wit. Whereas Shakespeare, however imperfect in the “whole” some of his works may be, is never tedious and never mean; whereas Milton, however dull he may be, is never low; Wordsworth, when his genius deserts him, falls beneath meanness and below dullness. He achieves the incredible {…}

[41v]

The consequences, yet unforeseen, of science will create new professions, mostly decorative and futile, and many people will be fit for them.

_______

… And those of us who grow dull with the effort to read Shaw or D’Annunzio can seek refuge with Mr. W. W. Jacobs, and sanity with Mr. Wills Croft and Dr. Austin Freeman.

_______

Regicide will be in order, because the killer of a king is more or less sure of immortality[1]. Governments may react, and bury him unnamed; but the terrible precedent of the Unknown Soldier will give to the crimes, political or mortal, of the future the right of belonging to a God of the Unknown Murderer. Women will weep his death and dream of how he was when living, and, as nothing of him is known, no disillusion can come upon the dream.

[19 – 41]

Heróstrato.

O génio é a loucura tornada sã pela diluição no abstracto, como um veneno convertido em medicamento pela mistura. O seu produto próprio é a novidade abstracta – isto é, a novidade que se conforma, no fundo, com as leis gerais da inteligência humana e não com as leis particulares da doença mental. A essência do génio é a inadaptação ao meio; é por isso que o génio (a não ser que seja acompanhado por talento ou sagacidade) é geralmente incompreendido pelo seu meio; e eu digo “geralmente” e não “universalmente”, porque muito depende do meio. Não é a mesma coisa ser um génio na Grécia antiga e na Europa moderna ou no mundo moderno.

Shakespeare era desconhecido como génio no seu tempo, pois os elevados, embora póstumos, louvores de Ben Jonson não são mais do que a elevada linguagem da época, destituída de significado e aplicada pelo mesmo Jonson a homens de quem ninguém hoje sabe nada – esse Lord Mounteagle de quem diz que “se mantinha como a inteligência dominante” (nada menos) desse tempo ou o próprio James I, {…} Shakespeare era admirado no seu tempo pela sua sagacidade, não enquanto um homem de génio. Como poderia ele ser admirado como um homem de génio? Era o criador de Falstaff que poderia ser compreendido; o criador de Hamlet não poderia ser. Se as facções anti-Stratfordianas se tivessem dado ao trabalho de perceber isso, muitas comparações absurdas com o louvor feito por Jonson ou por outros homens do seu tempo teriam sido impossíveis.

Shakespeare é o exemplo de grande génio e grande sagacidade ligado à insuficiência de talento. Ele é tão supremo na intuição que constitui o génio e na rapidez da estranheza que constitui a sagacidade quanto é insuficiente na construção e na coordenação que constitui o talento.

Milton é o exemplo da união de grande génio e grande talento. Ele tem a intuição do génio e o poder normativo do talento. Não possui nenhuma sagacidade; era, de facto, um pedante. Mas tinha a vontade firme do pedante, embora pesada.

Wordsworth, por exemplo, é a exemplificação do génio puro, o génio não aliado ao talento ou à sagacidade. Enquanto Shakespeare, ainda que algumas das suas obras sejam imperfeitas no “todo”, nunca é tedioso nem mau; enquanto Milton, ainda que seja monótono, nunca é baixo; Wordsworth, quando o génio o abandona, cai abaixo do mau e abaixo no monótono. Ele atinge a incrível {…}

[41v]

As consequências, ainda imprevistas, da ciência criarão novas profissões, maioritariamente decorativas e fúteis, e muitas pessoas serão adequadas a elas.

_______

… E aqueles de nós que achem aborrecido o esforço de ler Shaw ou D’Annunzio podem encontrar refúgio no Sr. W. W. Jacobs e sanidade no Sr. Wills Croft e no Dr. Austin Freeman.

_______

O regicídio estará na ordem do dia, porque o assassino de um rei encontra-se mais ou menos certo da imortalidade. Os governos poderão reagir e enterrá-lo sem nome; mas o terrível precedente de um Soldado Desconhecido dará aos crimes, políticos ou mortais, do futuro o direito de pertencer a um Deus do Assassino Desconhecido. As mulheres chorarão a sua morte e sonharão em como ele seria enquanto vivo, uma vez que nada se saberá dele, não poderá vir nenhuma desilusão sobre o sonho.

[1] immortality /his fair |*notoriety|\

Classificação

Dados Físicos

Dados de produção

Dados de conservação

Palavras chave

Documentação Associada

Publicação integral: Fernando Pessoa, Heróstrato e a Busca da Imortalidade, edição de Richard Zenith, Lisboa, Assírio & Alvim, 2000, pp. 145-147; 164-165.