Identificação

[BNP/E3, 14E – 69]

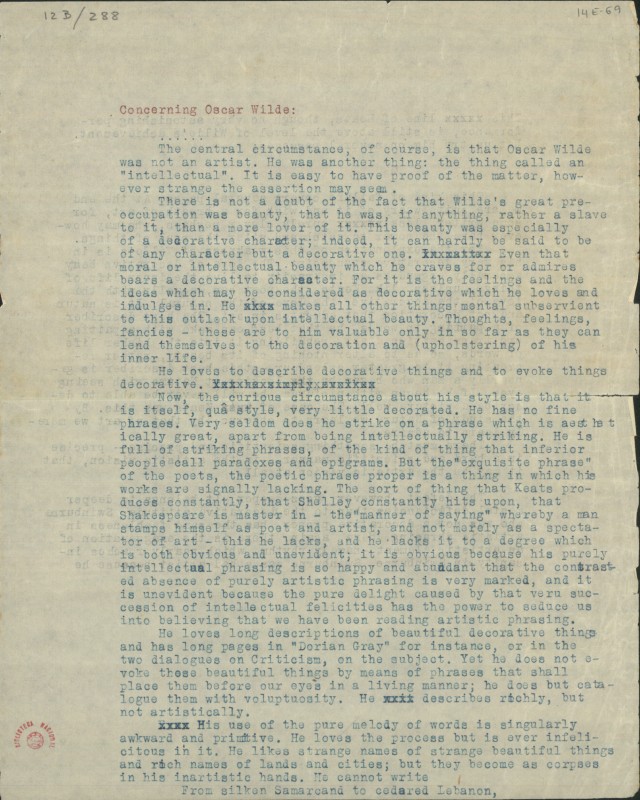

Concerning Oscar Wilde:

......

The central circumstance, of course, is that Oscar Wilde was not an artist. He was another thing: the thing called an “intellectual”. It is easy to have proof of the matter, however strange the assertion may seem.

There is not a doubt of the fact that Wilde’s great preoccupation was beauty, that he was, if anything, rather a slave to it, than a mere lover of it. This beauty was especially of a decorative character; indeed, it can hardly be said to be of any character but a decorative one. Even that moral or intellectual beauty which he craves for or admires bears a decorative character. For it is the feelings and the ideas which may be considered as decorative which he loves and indulges in. He makes all other things mental subservient to this outlook upon intellectual beauty. Thoughts, feelings, fancies – these are to him valuable only in so far as they can lend themselves to the decoration and (upholstering) of his inner life.

He loves to describe decorative things and to evoke things decorative.

Now, the curious circumstance about his style is that it is itself, quâ style, very little decorated. He has no fine phrases. Very seldom does he strike on a phrase which is aesthetically great, apart from being intellectually striking. He is full of striking phrases, of the kind of thing that inferior people call paradoxes and epigrams. But the “exquisite phrase” of the poets, the poetic phrase proper is a thing in which his works are signally lacking. The sort of thing that Keats produces constantly, that Shelley constantly hits upon, that Shakespeare is master in – the “manner of saying” whereby a man stamps himself as poet and artist, and not merely as a spectator of art – this he lacks, and he lacks it to a degree which is both obvious and unevident; it is obvious because his purely intellectual phrasing is so happy and abundant that the contrasted absence of purely artistic phrasing is very marked, and it is unevident because the pure delight caused by that very succession of intellectual felicities has the power to seduce us into believing that we have been reading artistic phrasing.

He loves long descriptions of beautiful decorative things and has long pages in “Dorian Gray” for instance, or in the two dialogues on Criticism, on the subject. Yet he does not evoke these beautiful things by means of phrases that shall place them before our eyes in a living manner; he does but catalogue them with voluptuosity. He describes richly, but not artistically.

His use of the pure melody of words is singularly awkward and primitive. He loves the process but is ever infelicitous in it. He likes strange names of strange beautiful things and rich names of lands and cities; but they become as corpses in his inartistic hands. He cannot write

From silken Samarcand to cedared Lebanon,

[69v]

This line of Keats, though no very astonishing, is still above the level of Wilde’s achievement. Let us try him on several passages:

Q Q Q Q

This kind of failure covers several pages. At the end we are quite weary of it and wish for a breath of art, for some writer, less purely clever perhaps, who may however have the power to catch and utter the soul of things.

For the explanation of this weakness of Wilde’s is in his very decorative standpoint. The love of decorative beauty generally engenders an incapacity to live the inner life of things, unless, like Keats, the poet has, equally with the love of the decorative, the love of the natural. It is nature and not decoration that educates in art. The best describer of a painting, in words, he that best can make with a painting une transposition d’art, rebuilding it into the higher life of words, so as to alter nothing of its beauty, rather recreating it to greater splendour – this best describer is generally a man who began by looking at Nature with seeing eyes. If he began with pictures, he will never be able to describe a picture well. The case of Keats was this. By the study of Nature we learn to observe; by that of art we merely learn to admire.

There must be something scientific and precise – precise in a hard and scientific manner – in the artistic vision, that it may be the artistic vision at all.

The defect, however, goes deeper. It belongs to deeper mental deficiencies than to the decorative attitude. Swinburne who was not a decorative proper, has the same feebleness in artistic phrasing. Here, again, there is the exaggeration of an artistic element – namely rhythm, which nearly reaches insanity in Swinburne. Swinburne was a bad artist because he {…}

[BNP/E3, 14E - 69]

Sobre Oscar Wilde:

......

A circunstância central, claro, é que Oscar Wilde não era um artista. Ele era outra coisa: a coisa chamada “intelectual”. É fácil ter provas do assunto, por mais estranha que possa parecer a afirmação.

Não há dúvida do facto de que a grande preocupação de Wilde era a beleza, que se ele era alguma coisa, era antes um escravo dela, do que um mero amante dela. Essa beleza era especialmente de carácter decorativo; na verdade, dificilmente se pode dizer que tem qualquer carácter além de decorativo. Mesmo aquela beleza moral ou intelectual que ele anseia ou admira tem um carácter decorativo. Pois são os sentimentos e as ideias que podem ser considerados decorativos que ele ama e a que se entrega. Ele torna todas as outras coisas mentais subservientes a essa perspectiva da beleza intelectual. Pensamentos, sentimentos, fantasias - para ele são valiosos apenas na medida em que podem servir para a decoração e (forro) da sua vida interior.

Ele adora descrever coisas decorativas e evocar coisas decorativas.

Ora, o facto curioso sobre o seu estilo é que ele próprio é, enquanto estilo, muito pouco decorado. Ele não tem frases bonitas. Muito raramente ele atinge uma frase que seja esteticamente grande, além de ser intelectualmente impressionante. Ele está cheio de frases marcantes, do tipo de coisa que as pessoas inferiores chamam de paradoxos e epigramas. Mas a “frase extraordinária” dos poetas, a frase poética propriamente dita, é algo que falta notavelmente às suas obras. O tipo de coisa que Keats produz constantemente, que Shelley constantemente descobre, em que Shakespeare é mestre - a “maneira de dizer” pela qual um homem se cunha como poeta e artista, e não apenas como um espectador de arte - isso ele não tem, e carece disso num grau que é óbvio e não evidente; é óbvio porque o seu fraseado puramente intelectual é tão feliz e abundante que a ausência contrastada de fraseado puramente artístico é muito marcada, e não é evidente porque o puro deleite causado por essa mesma sucessão de felicidades intelectuais tem o poder de nos seduzir a acreditar que lemos frases artísticas.

Ele adora longas descrições de belas coisas decorativas e tem longas páginas em “Dorian Gray”, por exemplo, ou nos dois diálogos sobre Crítica, acerca do assunto. No entanto, ele não evoca essas coisas belas por meio de frases que as colocam diante dos nossos olhos de uma maneira viva; ele apenas os cataloga com voluptuosidade. Ele descreve ricamente, mas não artisticamente.

O seu uso da pura melodia das palavras é singularmente estranho e primitivo. Ele adora o processo, mas é sempre infeliz nele. Ele gosta de nomes estranhos de coisas belas e ricas e nomes ricos de terras e cidades; mas eles tornam-se como cadáveres nas suas mãos inartísticas. Ele não consegue escrever

From silken Samarcand to cedared Lebanon,

[69v]

Este verso de Keats, embora não seja muito surpreendente, ainda está acima do nível daquilo que Wilde consegue atingir. Vamos testá-lo em várias passagens:

Q Q Q Q

Esse tipo de falha abrange várias páginas. No final, estamos bastante cansados disso e desejamos um sopro de arte, algum escritor, menos puramente inteligente talvez, que possa, entretanto, captar e expressar a alma das coisas.

Pois a explicação desta fraqueza de Wilde está no seu ponto de vista muito decorativo. O amor pela beleza decorativa geralmente engendra uma incapacidade de viver a vida interior das coisas, a menos que, como Keats, o poeta tenha, a par do amor pelo decorativo, o amor pelo natural. É a natureza e não a decoração que educa na arte. Aquele que melhor descreve uma pintura, em palavras, o que melhor consegue fazer com uma pintura une transposition d'art, reconstruindo-a na vida superior das palavras, de forma a não alterar nada na sua beleza, antes recriando-a num esplendor maior – este que descreve melhor é geralmente um homem que começou olhando para a Natureza com olhos que vêem. Se ele começou com imagens, nunca será capaz de descrever bem uma imagem. Este foi o caso de Keats. Pelo estudo da Natureza, aprendemos a observar; por meio da arte, aprendemos apenas a admirar.

Deve haver algo de científico e preciso - preciso de uma maneira dura e científica - na visão artística, para que possa de todo haver a visão artística.

O defeito, porém, é mais profundo. Pertence a deficiências mentais mais profundas do que a atitude decorativa. Swinburne, que não era um decorativo propriamente dito, tem a mesma fragilidade no fraseado artístico. Aqui, novamente, há o exagero de um elemento artístico – a saber, o ritmo, que chega quase à loucura em Swinburne. Swinburne era um péssimo artista porque ele {…}

Classificação

Dados Físicos

Dados de produção

Dados de conservação

Palavras chave

Documentação Associada

Publicação Integral: Pauly Ellen Bothe, Apreciações literárias de Fernando Pessoa, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, 2013, pp. 303-305.