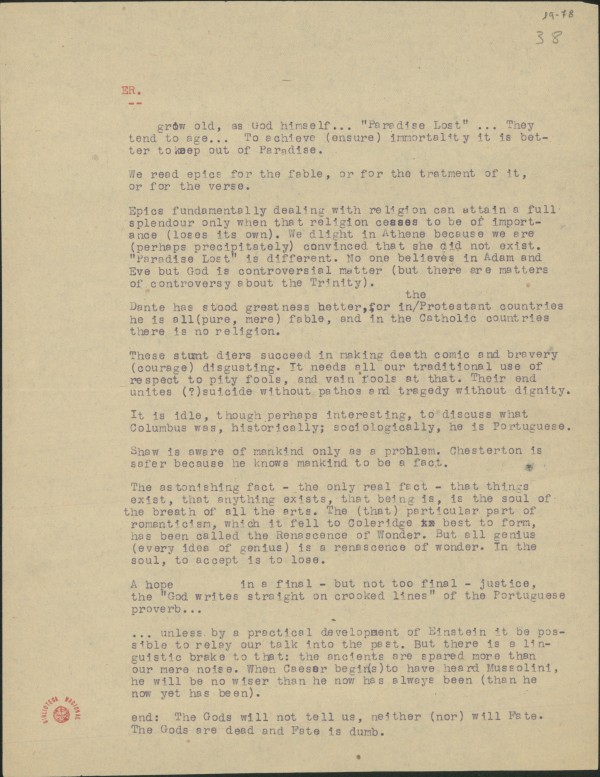

Identificação

[19 – 78]

Erostratus.

{…} grow old, as God himself… “Paradise Lost”… They tend to age… To achieve[1] immortality it is better to keep out of Paradise.

We read epics for the fable, or for the treatment of it, or for the verse.

Epics fundamentally dealing with religion can attain a full splendour only when that religion ceases to be of importance[2]. We delight in Athene because we are (perhaps precipitately) convinced that she did not exist. “Paradise Lost” is different. No one believes in Adam and Eve but God is controversial matter[3].

Dante has stood greatness better, for in the Protestant countries he is all[4] fable, and in the Catholic countries there is no religion.

These stunt diers succeed in making death comic and bravery[5] disgusting. It needs all our traditional use of respect to pity fools, and vain fools at that. Their end unites (?) suicide without pathos and tragedy without dignity.

It is idle, though perhaps interesting, to discuss what Columbus was, historically; sociologically, he is Portuguese.

Shaw is aware of mankind only as a problem. Chesterton is safer because he knows mankind to be a fact.

The astonishing fact – the only real fact – that things exist, that anything exists, that being is, is the soul of the breath of all the arts. The[6] particular part of romanticism, which it fell to Coleridge best to form, has been called the Renascence of Wonder. But all genius[7] is a renascence of wonder. In the soul, to accept is to lose.

A hope {…} in a final – but not too final – justice, the “Gods writes straight on crooked lines” of the Portuguese proverb…

…unless by a practical development of Einstein it be possible to relay our talk into the past. But there is a linguistic brake to that: the ancients are spared more than our mere noise. When Caesar begins[8] to have heard Mussolini, he will be no wiser than he now has always been[9].

end: The Gods will not tell us, neither[10] will Fate. The Gods are dead and Fate is dumb.

[19 – 78]

Heróstrato.

Envelhecem como o próprio Deus… “Paraíso Perdido”… Tendem a envelhecer… Para alcançar a imortalidade é melhor ficar fora do Paraíso.

Lemos os épicos pela fábula ou pelo seu tratamento ou pelo verso.

Os épicos que fundamentalmente lidem com religião podem atingir o pleno esplendor apenas quando essa religião deixa de ter importância. Deleitamo-nos com Atena porque estamos (talvez precipitadamente) convencidos de que ela não existe. O “Paraíso Perdido” é diferente. Ninguém acredita em Adão e Eva, mas Deus é uma matéria controversa.

Dante ficou melhor no que respeita à grandeza, pois nos países protestantes ele é totalmente fábula e nos países católicos não existe religião.

Estas mortes acrobáticas podem conseguir tornar a morte cómica e a bravura repugnante. É necessário todo o nosso uso do respeito para sentir pena dos tolos e daqueles tolos que têm vaidade nisso. O seu fim reúne suicídio sem afecção e a tragédia sem dignidade.

É vão, embora talvez interessante, discutir o que Colombo era historicamente; sociologicamente, ele era português.

Shaw está ciente da humanidade apenas enquanto um problema. Chesterton é mais seguro, porque sabe que a humanidade é um facto.

O facto impressionante – o único facto real – de que as coisas existem, de que algo existe, de que o ser existe, é a alma do fôlego de todas as artes. Aquela parte especifica do romantismo, que coube a Coleridge formar melhor, foi chamada de Renascimento do Maravilhoso. Mas todo o génio é um renascimento do maravilhoso. Na alma, aceitar é perder.

Uma esperança {…} numa justiça final – mas não demasiado final –¸os “Deuses escrevem direito por linhas tortas” do provérbio português…

… a não ser que por um desenvolvimento prático de Einstein seja possível fazer recuar a nossa conversa ao passado. Mas existe um impedimento linguístico a isso: os antigos são poupados a mais do que o nosso mero ruído. Quando César começa a ouvir Mussolini, ele não será mais sábio do que sempre tem sido.

fim: Os Deuses não nos dirão, nem o Destino. Os Deuses estão mortos e o Destino é surdo.

[1] achieve /(ensure)\

[2] ceases to be of importance /(loses its own)\

[3] but God is controversial matter /(but there are matters of controversy about the Trinity)\

[4] all /(pure, mere)\

[5] bravery /(courage)\

[6] The /(that)\

[7] all genius /(every idea of genius)\

[8] begin/(s)\

[9] than he now has always been /(than he now yet has been)\

[10] neither /(nor)\