Identificação

[19 – 59]

Erostratus.

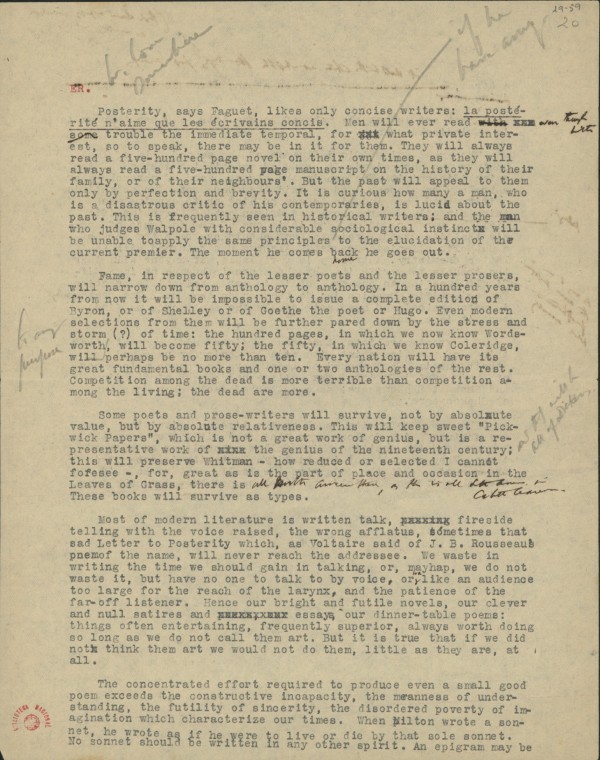

Posterity, says Faguet, likes only concise writers: la posterité n’aime que les écrivains concis. Men will ever read even though with trouble the immediate temporal, for what private interest, so to speak, there may be in it for them. They will always read a five-hundred page novel on their own times, as they will always read a five-hundred page manuscript on the history of their family, or of their neighbours’. But the past will appeal to them only by perfection and brevity. It is curious how many a man, who is a disastrous critic of his contemporaries, is lucid about the past. This is frequently seen in historical writers; and the man who judges Walpole with considerable sociological instinct will be unable to apply the same principles if he have any to the elucidation of the current premier. The moment he comes back[1] he goes out.

Fame, in respect of the lesser poets and the lesser prosers, will narrow down from anthology to anthology. In a hundred years from now it will be impossible to issue a complete edition of Byron, or of Shelley or of Goethe the poet or Hugo. Even modern selections from them will be further pared down by the stress and storm (?) of time: the hundred pages, in which we now know Wordsworth to any purpose, will become fifty; the fifty, in which we know Coleridge, will perhaps be no more than ten. Every nation will have its great fundamental books and one or two anthologies of the rest. Competition among the dead is more terrible than competition among the living; the dead are more.

Some poets and prose-writers will survive, not by absolute value, but by absolute relativeness. This will keep sweet “Pickwick Papers”, which is not a great work of genius, but is a representative work of the genius of the nineteenth century and this will be all of Dickens; this will preserve Whitman – how reduced or selected I cannot foresee – , for, great as is the part of place and occasion in the Leaves of Grass, there is all North America there, as there is all Latin America in Catullo Cearense. These books will survive as types.

Most of modern literature is written talk, fireside telling with the voice raised, the wrong afflatus, sometimes that sad Letter to Posterity which, as Voltaire said of J. B. Rousseau’s poem of the name, will never reach the addressee. We waste in writing the time we should gain in talking, or, mayhap, we do not waste it, but have no one to talk to by voice, or we like an audience too large for the reach of the larynx, and the patience of the far-off listener. Hence our bright and futile novels, our clever and null satires and essays, our dinner-table poems: things often entertaining, frequently superior, always worth doing so long as we do not call them art. But it is true that if we did not think them art we would not do them, little as they are, at all.

The concentrated effort required to produce even a small good poem exceeds the constructive incapacity, the meanness of understanding, the futility of sincerity, the disordered poverty of imagination which characterize our times. When Milton wrote a sonnet, he wrote as if he were to live or die by that sole sonnet. No sonnet should be written in any other spirit. An epigram may be

[59v]

a straw, it should be the straw at which the dying poet grasps.

Great art is not the work of journalists, whether they write in periodicals or not.

The great scientific influence of the second half of last century was unreceived. It produced materialism instead of the scientific spirit. The man in the street heard of phrenology or astrology or alchemy, and he said they were rot. The scientific spirit would have led him to say nothing or to examine each thing directly. Phrenology (though absurd and perhaps |*even clear as something put by side and shy|) was driven out of the scientific field by mere religious prejudice |*as may be seen in the coarse quality for trueness with anomaly|, and it is one of the delights of Nemesis that its gradual reinstalment should have been the work of a Catholic alienist, Grasset. Alchemy has returned with the latter chemistry. Astrology is verifiable, if anyone will take the trouble to verify it. Why the stars influence us is a difficult question to answer, but it is not a scientific question. The scientific question is: do they or do they not? The reason why is metaphysical and need not trouble the fact, once we find that it is a fact.

The great novelists, the great artists and the great other things of our time point with pride to their fortunes and to their public. They should at least have the courage to sneer at their past inferiors. Wells should laugh at Fielding and Shaw at Shakespeare; as a matter of fact, Shaw does laugh at Shakespeare.

They have celebrity, such as the time can give; they have the fortune which follows upon that celebrity; they have the honours and the position which follow upon either or both of those. They cannot want immortality. What the Gods give they sell, the Greeks said. And English children are told that they cannot have the cake they eat.

|*I have no hatred, as an absolute hate to give… I would {…} then Pickwick Papers. It is resolutely in Dickens to impose a deliberate hate to the glad confession.|

- W. Jacobs

|Heaven| is surely large enough for the Night Watchman and my soul.

[19 – 59]

Heróstrato.

A posteridade, diz Faguet, ama apenas os escritores concisos: la posterité n’aime que les écrivains concis. Os homens lerão sempre, embora com dificuldade, o temporalmente imediato, pelo interesse privado que, por assim dizer, possa existir para eles. Lerão sempre um romance de quinhentas páginas sobre o seu próprio tempo, assim como sempre lerão um manuscrito de quinhentas páginas sobre a história da sua família ou dos seus vizinhos. Mas o passado apenas os atrairá pela perfeição e brevidade. É curioso quantos homens, que são desastrosos críticos dos seus contemporâneos, são lúcidos sobre o passado. Vê-se isto frequentemente em escritores históricos; e o homem que julga Walpole com um considerável instinto sociológico será incapaz de aplicar os mesmos princípios, se tiver alguns, à elucidação do actual primeiro-ministro. No momento em que regressa, sai logo.

A fama, a respeito dos poetas menores e dos prosadores menores, diminuirá de antologia para antologia. Daqui a cem anos será impossível publicar uma edição completa de Byron, de Shelley, de Gothe enquanto poeta ou de Hugo. Mesmo as modernas selecções deles serão ainda mais reduzidas pela tensão e tormenta (?) do tempo: as cem páginas, em que agora, para todo o efeito, conhecemos Wordsworth, tornar-se-ão cinquenta; as cinquenta, em que conhecemos Coleridge, não serão talvez mais do que dez. Cada nação terá os seus grandes livros fundamentais e uma ou duas antologias para o resto. A competição entre os mortos é mais terrível do que a competição entre os vivos; os mortos são mais.

Alguns poetas e prosadores sobreviverão, não por valor absoluto, mas por absoluta relatividade. Isto tornará doce os “Pickwick Papers”, que não é uma excepcional obra de génio, mas é uma obra representativa do génio do século XIX e isso será tudo de Dickens; isto preservará Whitman – quão reduzido ou seleccionado não consigo prever –, pois, como é grande a participação do lugar e da ocasião em Leaves of Grass, existe aí toda a América do Norte, tal como existe toda a América Latina em Catulo Cearense. Estes livros sobreviverão como tipos.

A maioria da literatura moderna é conversa escrita, dizer contos à lareira com a voz elevada, a inspiração errada, por vezes aquela triste Carta à Posteridade que, como Voltaire disse do poema com o nome de J. B. Rosseau, nunca chegará ao destinatário. Perdemos na escrita o tempo de deveríamos ganhar a falar ou talvez não o desperdicemos, mas não tenhamos ninguém para falar com a voz ou gostemos de uma audiência demasiado vasta para o alcance da laringe e para a paciência do remoto ouvinte. Daí os nossos romances brilhantes e fúteis, as nossas sátiras e ensaios inteligentes e nulos, os nossos poemas de mesa de jantar: coisas frequentemente para entreter, frequentemente superiores, sempre dignas de serem feitas desde que não lhes chamemos arte. Mas é verdade que, se não pensássemos que elas fossem arte, não as faríamos, por muito pequenas que sejam.

O esforço concentrado requerido para produzir mesmo um pequeno bom poema excede a incapacidade construtiva, a mediocridade de compreensão, a futilidade de sinceridade, a pobreza desordenada da imaginação que caracteriza o nosso tempo. Quando Milton escrevia um soneto, escrevia como se fosse viver ou morrer por esse único soneto. Nenhum soneto deveria ser escrito em qualquer outro espírito. Um epigrama pode ser

[59v]

uma palha, mas deveria ser uma palha a que se agarra o poeta moribundo.

A grande arte não é obra de jornalistas, quer eles escrevam em periódicos ou não.

A grande influência científica da segunda metade do último século não foi acolhida. Produziu o materialismo em vez do espírito científico. O homem da rua ouviu falar da frenologia, astrologia ou alquimia e disse que eram tolices. O espírito científico tê-los-ia levado a não dizer nada ou a examinar cada coisa directamente. A frenologia (embora absurda e talvez |*até como algo a ser posto claramente de lado e acanhado|) foi posta fora do domínio científico por mero preconceito religioso |*como pode ser constatado na qualidade grosseira como verdadeira perante a anomalia|, e é um dos prazeres de Némesis que a sua recuperação gradual tenha sido a obra de um católico alienista, Grasset. A alquimia voltou com a mais recente química. A astrologia é verificável, se alguém se desse ao trabalho de a verificar. Porque é que as estrelas nos influenciam é uma questão difícil de responder, mas não é uma questão científica. A questão científica é: fazem-no ou não? A razão porque o fazem é metafísica e não perturba do facto, uma vez que tenhamos constatado que é um facto.

Os grandes romancistas, os grandes artistas e os grandes outras coisas do nosso tempo apontam com orgulho para as suas fortunas e para o seu público. Deveriam, pelo menos, ter a coragem de zombar dos seus inferiores do passado. Wells deveria rir-se de Fielding e Shaw de Shakespeare; com efeito, Shaw ri-se de Shakespeare.

Eles têm celebridade, tanto quanto o tempo o pode dar; têm a fortuna decorrente dessa celebridade; têm as honras e a posição que se segue de uma delas ou de ambas. Não podem desejar a imortalidade. Os Deuses vendem o que dão, diziam os gregos. E diz-se às crianças inglesas que não podem ficar com o bolo e comê-lo.

|*Não tenho um ódio absoluto, enquanto ódio absoluto para atribuir… Deveria {…}, então, os Pickwick Papers. Está resolutamente em Dickens a imposição de um ódio deliberado à alegre confissão.|

- W. Jacobs

|O céu| é certamente lago o suficiente para o Vigilante Nocturno e para a minha alma.

[1] back /home\

Classificação

Dados Físicos

Dados de produção

Dados de conservação

Palavras chave

Documentação Associada

Fernando Pessoa, Heróstrato e a Busca da Imortalidade, edição de Richard Zenith, Lisboa, Assírio & Alvim, 2000, pp. 180-183; 207.