Identificação

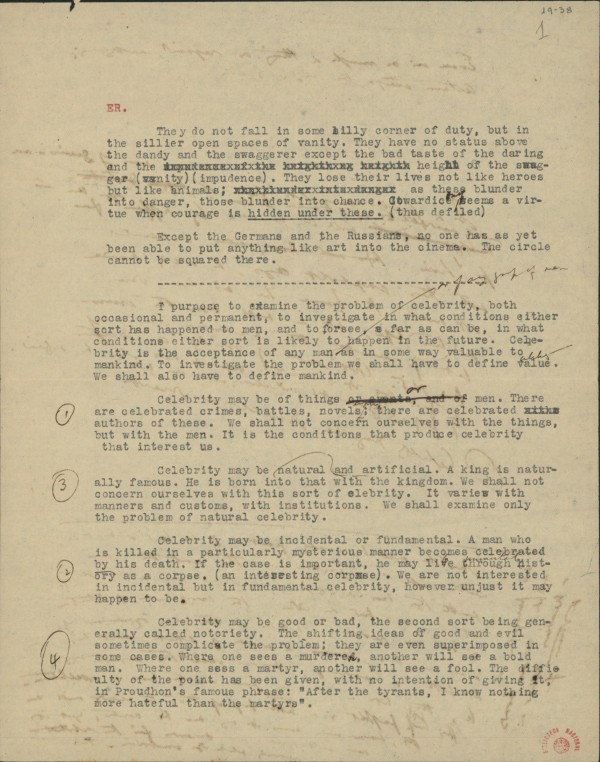

[19 – 38]

Erostratus.

They do not fall in some silly corner of duty, but in the sillier open spaces of vanity. They have no status above the dandy and the swaggerer except the bad taste of the daring and the height of the swagger[1]. They lose their lives not like heroes but like animals; as these blunder into danger, those blunder into chance. Cowardice only seems a virtue when courage is hidden under these[2].

Except the Germans and the Russians, no one has as yet been able to put anything like art into the cinema. The circle cannot be squared there.

-----------------------------------------------

I purpose to examine the problem of celebrity, both occasional and permanent, to investigate in what conditions either sort has happened to men, and to foresee, as far as can be, in what conditions either sort is likely to happen in the future. Celebrity is the acceptance of any man or of any group of men as in some way valuable to mankind. To investigate the problem we shall have to define value[3]. We shall also have to define mankind.

(1) Celebrity may be of things or of men. There are celebrated crimes, battles, novels, empires; there are celebrated authors of these. We shall not concern ourselves with the things, but with the men. It is the conditions that produce celebrity that interest us.

(2) Celebrity may be incidental or fundamental. A man who is killed in a particularly mysterious manner becomes celebrated by his death. If the case is important, he may live through history as a corpse[4]. We are not interested in incidental but in fundamental celebrity, however unjust it may happen to be.

(3) Celebrity may be artificial and natural. A king is naturally famous. He is born into that with the kingdom. We shall not concern ourselves with this sort of celebrity. It varies with manners and customs, with institutions. We shall examine only the problem of natural[5] celebrity.

(4) Celebrity may be good or bad, the second sort being generally called notoriety. The shifting ideas of good and evil sometimes complicate the problem; they are even superimposed in some cases. Where one sees a murderer, another will see a bold man. Where one sees a martyr, another will see a fool. The difficulty of the point has been given, with no intention of giving it, in Proudhon’s famous phrase: “After the tyrants, I know nothing more hateful than the martyrs”.

[38v]

Even in so simple a thing as regicide, nothing is certain except[6] the king’s death.

In a possible socialistic future, the man of genius – an individual inadapted to any of the action or leisure of the hive, and therefore the one beggar there – will be famous by difference from the hive. In contrast with this capitalist age, he will have at once the fame he is here denied in |his| life; but he will have the consolation of maintaining the economic tradition of his kind. No mode of society can adorn the fact that it is society: superiority will always be inferior. The proof, and the[7] incidental reservations, will be seen further on.

(5) Celebrity may be derivate or direct.

______________________________________________________________________

Chesterton would be really great if he had what we Latins call “composition” – the notion that a written thing has a beginning, a middle and an end: that, literature being fed on ideas, the composition of literature is fed on reasoning, which is an organism of ideas – that a work of literature must be, at birth, a reasoning, however void the argument may be, that has a body, a poem must have a skeleton. This brief[8] pamphlet is a little[9] proof of this: the reader will see that, however much wordiness it may seem to contain, yet it never really digresses, nor swerves from the abstract reasoning which it embodies – that no paragraph is misplaced, nor are brooding or weakness allowed in the stream of {…}

[19 – 38]

Heróstrato.

Eles não caiem em nenhuma esquina estúpida do dever, mas nos espaços abertos ainda mais estúpidos da vaidade. Não têm nenhum estatuto superior ao dândi e ao arrogante, excepto o mau gosto da ousadia e a altivez do arrogante. Perdem as suas vidas não como heróis, mas como animais; enquanto estes tropeçam no perigo, aqueles tropeçam no acaso. Apenas a covardia parece uma virtude quando a coragem se esconde debaixo destes.

Excepto os alemães e os russos, ninguém foi ainda capaz de colocar algo como arte no cinema. Não é possível fazer aí a quadratura do círculo.

-----------------------------------------------

Proponho-me examinar o problema da celebridade, tanto ocasional quanto permanente, investigar em que condições ambos os tipos ocorreram ao homem e prever, tanto quanto possível, em que condições ambos os tipos poderão vir a ocorrer no futuro. A celebridade é a aceitação de um homem ou grupo de homens como, de algum modo, valiosos para a humanidade. Para investigar o problema temos de definir o valor. Temos também de definir a humanidade.

(1) A celebridade pode ser de coisas ou de homens. Existem crimes, batalhas, romances, impérios célebres; existem os autores célebres destes. Não nos devemos ocupar das coisas, mas dos homens. O que nos interessa são as condições que produzem a celebridade.

(2) A celebridade pode ser incidental ou fundamental. Um homem que é morto de uma maneira particularmente misteriosa torna-se célebre pela sua morte. Se o caso for importante, poderá sobreviver ao longo da história como um cadáver. Não estamos interessados na celebridade incidental, mas na fundamental, independente de quão injusta possa ser.

(3) A celebridade pode ser artificial e natural. Um rei é naturalmente famoso. Ele nasceu assim com o reino. Não nos devemos preocupar com este tipo de celebridade. Ela varia com os usos e os costumes, com as instituições. Devemos examinar apenas o problema da celebridade artificial.

(4) A celebridade pode ser boa ou má, sendo o segundo tipo geralmente chamado de notoriedade. As ideias inconstantes de bem e de mal, por vezes, complicam o problema; são até sobrepostas, em alguns casos. Onde uma pessoa vê um assassino, outra verá um homem de coragem. Onde uma pessoa vê um mártir, outra verá um tolo. A dificuldade a este respeito foi-nos transmitida, sem a intenção de o ser, na famosa frase de Proudhon: “Depois do tirano, não conheço nada mais odioso do que os mártires”.

[38v]

Mesmo numa coisa tão simples quanto o regicídio, nada é certo excepto a morte do rei.

Num possível futuro socialista, o homem de génio – um indivíduo inadaptado a qualquer acção ou lazer da colmeia e, portanto, o único mendigo desse lugar – será famoso pela diferença da colmeia. Em contraste como esta era capitalista, terá imediatamente a fama que lhe é negada aqui na sua vida; mas terá a consolação de manter a tradição económica da sua espécie. Nenhum modo de sociedade pode adornar o facto de que é sociedade: a superioridade será sempre inferior. A prova, e as reservas incidentais, mostrar-se-ão mais adiante.

(5) A celebridade pode ser derivada ou directa.

______________________________________________________________________

Chesterton seria realmente óptimo se tivesse aquilo que nós, latinos, chamamos “composição” – a noção de que o que é escrito tem um princípio, um meio e um fim: que, sendo a literatura alimentada por ideias, a composição da literatura é alimentada pelo raciocínio, que é um organismo de ideias – que um trabalho em literatura deve ser, à nascença, um raciocínio, por mais vazio que seja o argumento, que tem um corpo, que um poema deve ter um esqueleto. Este breve panfleto é uma pequena prova disto: o leitor verá que, por mais palavreado que pareça conter, contudo, nunca se desvia realmente, nem se afasta do raciocínio abstracto que incorpora – que nenhum parágrafo se encontra fora do lugar, nem são permitidas cismas ou fraquezas do decurso de {…}

[1] swagger /(vanity)\ /(impudence)\

[2] hidden under these. /(thus defiled)\

[3] value /celebrity\

[4] live through history /be immortal\ as a corpse /(an interesting corpse)\

[5] A palavra «natural», neste lugar, trata-se de um possível lapso. Onde figura a palavra «natural» deveria figurar «artificial», como constata Richard Zenith em: Fernando Pessoa, Heróstrato e a Busca da Imortalidade, edição de Richard Zenith, Lisboa, Assírio & Alvim, 2000, pp. 127, 201. Assim sendo, na tradução utilizaremos a palavra «artificial» no lugar da palavra «natural».

[6] except /save\

[7] and the /with its\

[8] brief /little\

[9] little /modest\

Classificação

Dados Físicos

Dados de produção

Dados de conservação

Palavras chave

Documentação Associada

Publicação integral: Fernando Pessoa, Heróstrato e a Busca da Imortalidade, edição de Richard Zenith, Lisboa, Assírio & Alvim, 2000, pp. 127-128; 145; 161; 165-166.